Citizen science databases can be an excellent tool for getting to know the flora and fauna present within your surrounding environment, and these days there are plenty of platforms with publicly accessible databases to which you can contribute yourself and view previous records.

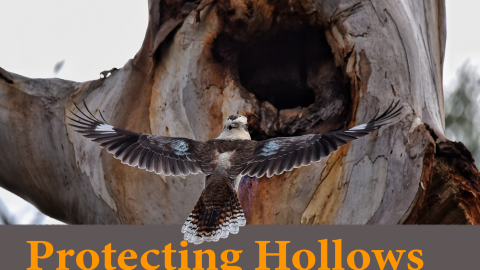

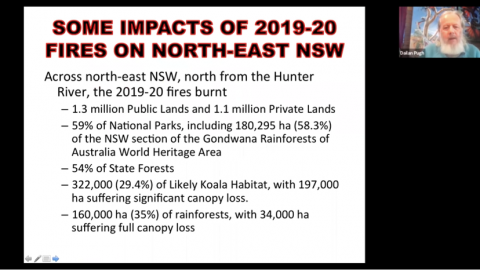

By contributing to these datasets with information gathered on your own property (or wherever you happen to identify a plant or animal), you can build up these datasets that are not only visible to and used by other people for their own personal use, but also by researchers who may be using this data in their academic work. A wealth of research relating to the effects of bushfires, climate change, and numerous other disturbances have been facilitated using large citizen science databases, using data gathered by the general public. These databases can be used to track habitat suitability and changes in faunal distributions for conservation purposes, guiding efforts to protect our native wildlife and plant communities. For example, areas with many hollows and significant habitat trees may be prioritised for conservation action by the government – and these areas can now be identified using the tree hollows dataset on iNaturalist.

So, if you’re interested in using these datasets yourself, or perhaps even contributing to them alongside thousands of other people, you have a few choices as to what platform to use. The aforementioned iNaturalist Australia platform (also available as an app), which is connected to the wider global iNaturalist Network and is supported by CSIRO, is a great platform to look at. All data entered into iNaturalist is also fed into the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA), the largest citizen science database in the country, which is commonly used by researchers. The ALA database has over 100,000,000 records across over 10,000 datasets, so it is certain that you’ll find some previous records in your local area if you use this site to view previous data. The site has numerous helpful tools such as maps of previous records and the ability to search via species, taxon, and more.

However, while Atlas of Living Australia is useful for retrieving a much larger dataset, iNaturalist allows for the entry of your own sightings, and acts as social platform within which you can observe and discuss other people’s sightings – effectively a Facebook for naturalists! Furthermore, while there are fewer sightings recorded in iNaturalist overall (just over 4,000,000), it does make it easy to access and contribute to specific datasets which can be highly valuable. For example, check out the award-winning Environment Recovery Project dataset, which is tracking biodiversity and floral/faunal assemblages in areas recovering from the black summer bushfires.

You may have already seen our article on how community members who attended the Nature Conservation Council Bushfire Program’s recent workshop in the Kangaroo Valley set up an excellent tree hollows and significant habitat trees dataset on iNaturalist, which is another excellent dataset to take a look at. The article can be accessed here.

So, take a look at these datasets, as well as any others that pique your interest. See what others have found in your local area, and perhaps add some entries yourself!

Image by David Clode via Unsplash